Sara could not believe this was her first day as a substitute teacher for 2nd grade. This was supposed to be an easy day. They were practicing for the standardized test required by the state. The number two pencils were sharpened. She had passed out the sheets for bubbling in their answers. The students were busy bubbling in their names. Out of nowhere, she gets this question.

“What is sex?”

Sara stares at the 8-year-old boy with something between disbelief and fear on her face. She thought of how she herself learned about “the birds and the bees.” This was not the place for that conversation. She didn’t know what to do. Why was this 8-year-old boy making trouble? She had heard that students give substitute teachers a hard time.

Sara took a deep breath. She steeled herself for the difficult day ahead, and then did the only thing she could think of.

“What do you want to know about sex, Bobby?”

“Right here on the form it says, ‘sex.’ What does it mean?”

Sara exhaled a huge sigh of relief. This was a question she could answer.

“The ‘M’ is male, and that’s for boys. The ‘F’ is for female, and that’s for girls.”

“Oh,” said Bobby, as he diligently filled in the bubble on his sheet.

What are your assumptions?

Sara’s story is a funny anecdote about assumptions. Stories are filled with assumptions.

In fact, we rely on them as we tell our stories, give our lectures, go about our day. We don’t want to spell out every detail. We rely on our listeners to fill in the gaps. Too much unnecessary detail will wear our audience out, but not enough … leads to confusion. The detail that is needed might change depending on the audience. Eight-year-old Bobby needs different information than a 25-year-old teacher to understand “sex” when he is filling out a form.

How do you avoid confusing your audience?

Know your audience. Avoid unnecessary jargon. See the story from the audience’s point of view. And finally … practice … get feedback … practice … get feedback … practice.

In oral storytelling, we learn to tell stories by telling them out loud to an audience. The words on the page can have a very different meaning when they are said out loud with tone of voice and gestures. Public speaking is a conversation, but only one person is talking (with words). The audience communicates with the speaker through their own non-verbal responses.

In some sense, as the speaker, we have an idea of what the listeners are thinking and how they are experiencing our words by their non-verbal responses. We can respond appropriately in the moment, like Sara in the example above. What did Sara do? She asked for more information to see if her assumption was correct. Just like Sara, we can ask for feedback and respond to it. Learning to interpret and incorporate feedback is an essential skill in developing stories and speeches.

What assumptions do you make about your audience? Are they true? What assumptions do your listeners make about you? Do you need to clear them up? Is there a gap between what you are saying and what the audience is hearing? If the goal is communication, change how you say it and connect to the audience.

The beautiful thing about storytelling as an oral performance art is that stories get to change and grow from one telling to the next. I let go of what I think I said … and focus on what the audience heard. How can I craft the telling to more clearly get my meaning and message across?

“What is sex?” makes a funny story of Sara expecting one meaning and getting another. In conversation, we get a chance to clarify misunderstandings in the moment. In public speaking and storytelling performance, we don’t always get to clarify what we mean in the moment, but we can respond to feedback to improve the next performance.

Tips on Crafting Your Story

Know your audience. Practice telling. Ask for feedback. Clear up misunderstandings in the next telling. Repeat.

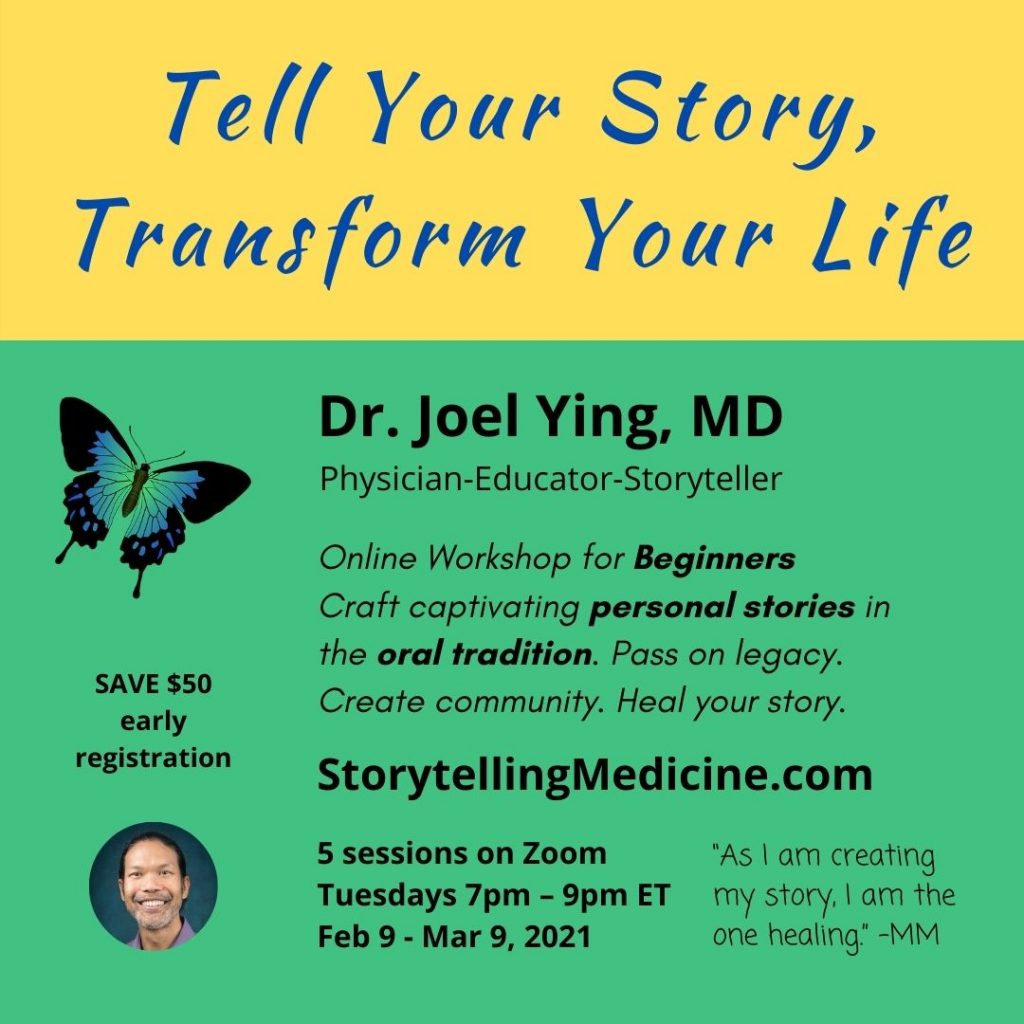

Learn more about crafting in the online workshop at StorytellingMedicine.com.