The sound of screeching brakes is followed by a thunderclap of crunching metal. The unexpected crash cuts through the pleasant background of music and chatter. My friend and I were just making our way from the car in the parking lot to the restaurant in the outdoor shopping center. My mind processes the sounds for a moment. Car accident. Intersection, beyond the hedges, 2 blocks away. I glimpse part of the traffic light. I imagine the intersection that I drive through several times a week.

The friend standing with me stops his conversation mid-sentence.

“Should we see if we can help?” he asks.

Even though I’m a doctor, this was not my first thought. I live in a sprawling city, and the emergency responders will be there soon. I don’t go chasing ambulances. I help when the problem is right in front of me, but I don’t look for trouble. My doctor training taught me to treat problems, but my parental training taught me to avoid them. When you grow up in a place where violence and trouble is expected, you don’t go looking for it.

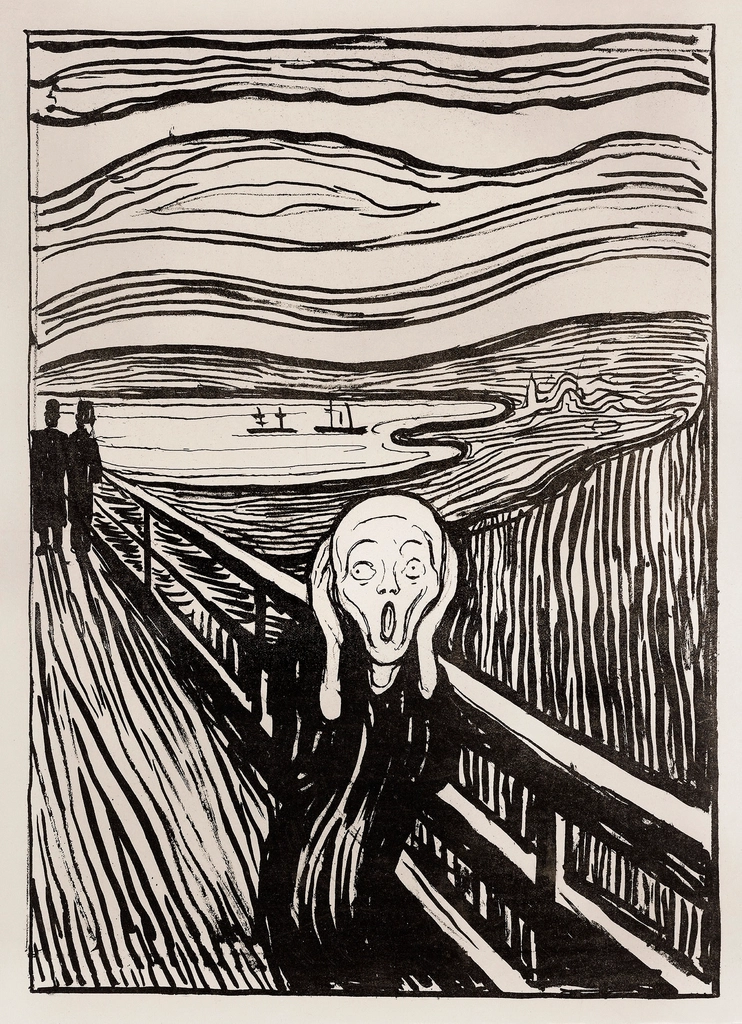

There was a momentary silence in the distance that felt like the world came to a stop. But a few seconds later, cutting through this silence was a bloodcurdling scream.

My friend takes off running.

I flash back to my time in the Labor and Delivery ward as a medical student. Screaming is a good sign. The newborn has good lungs. He will live. It’s the ones that don’t scream, that don’t breathe; those are the ones that we worry about. I can’t stop the images of the newborns that needed resuscitation from flashing through my mind. When you transfer a newborn to the ICU, you don’t always find out how their story ends. I hope they made it.

Today’s screaming pauses only momentarily for a breath and starts again. I register it as female. There is a sense of hysteria. Good lungs, I think to myself. She will live.

I follow my friend who is already running towards the intersection, spurred on by the screaming. I walk briskly behind him, not feeling the same urgency. I stop short as I arrive close enough to survey the scene minutes after him.

Cars stopped at the intersection. There is a young woman, likely a college student from the nearby university, long brown hair. White car smashed trying to make a wide left turn. She is standing in front of another smashed car. I can’t tell the color in the setting sun. Her gaze shifts between her car and the other car, both with some mangled metal. Her scream is steady, throaty, and filled with emotional pain. But not my emotion. I am trained as a doctor. I survey the scene with a calm mind. Am I needed here?

Sitting on the curb is a man in his late twenties, wearing a black long-sleeve shirt, probably leaving or going to work at a restaurant. He is stocky, short black hair, face buried in his hands, his very different response of disbelief in this sudden moment that has changed the trajectory of the evening, an impact that connects two cars and two lives from two very separate worlds. There are no bodily injuries, unless you look at the mangled cars. Other cars are navigating the blocked intersection to drive around the accident. Others have stopped to check if anyone is injured. Someone is standing a few feet from the screaming girl, wondering if there is something that she can do to help.

My friend has also assessed the scene from across the 5 lanes of the intersection up ahead of me. He looks at me. “Should we go across?” I say that they will be ok and gesture that we should return. We silently walk back to the shopping center. We hear sirens in the far distance that will soon arrive.

Inside the restaurant, the sound of the crash did not penetrate the walls, did not interrupt the laughter around the bar, did not halt the rush of the servers taking orders and bringing out food. We join others at the restaurant. My friend tells them about the accident and wonders how I could be so calm.

“She’s got good lungs,” I say. “She will be ok.”