“Clunk.” The second set of double doors automatically locked behind me with an audible delayed electric thud. I looked up at the clerk at the nursing station. A sudden irrational fear went through my mind, “What if she doesn’t recognize me on the way out?” I’m a medical student, and this is a psyche ward. I could be locked in here forever. The clerk smiled at me. I smiled and stared back at her long enough to ensure she would recognize my face and the short white coat that said, “I’m a medical student.” I will be on this rotation for a month. Today, I meet my mentor. She will arrange my experience of the different aspects of psychiatry, including this inpatient ward.

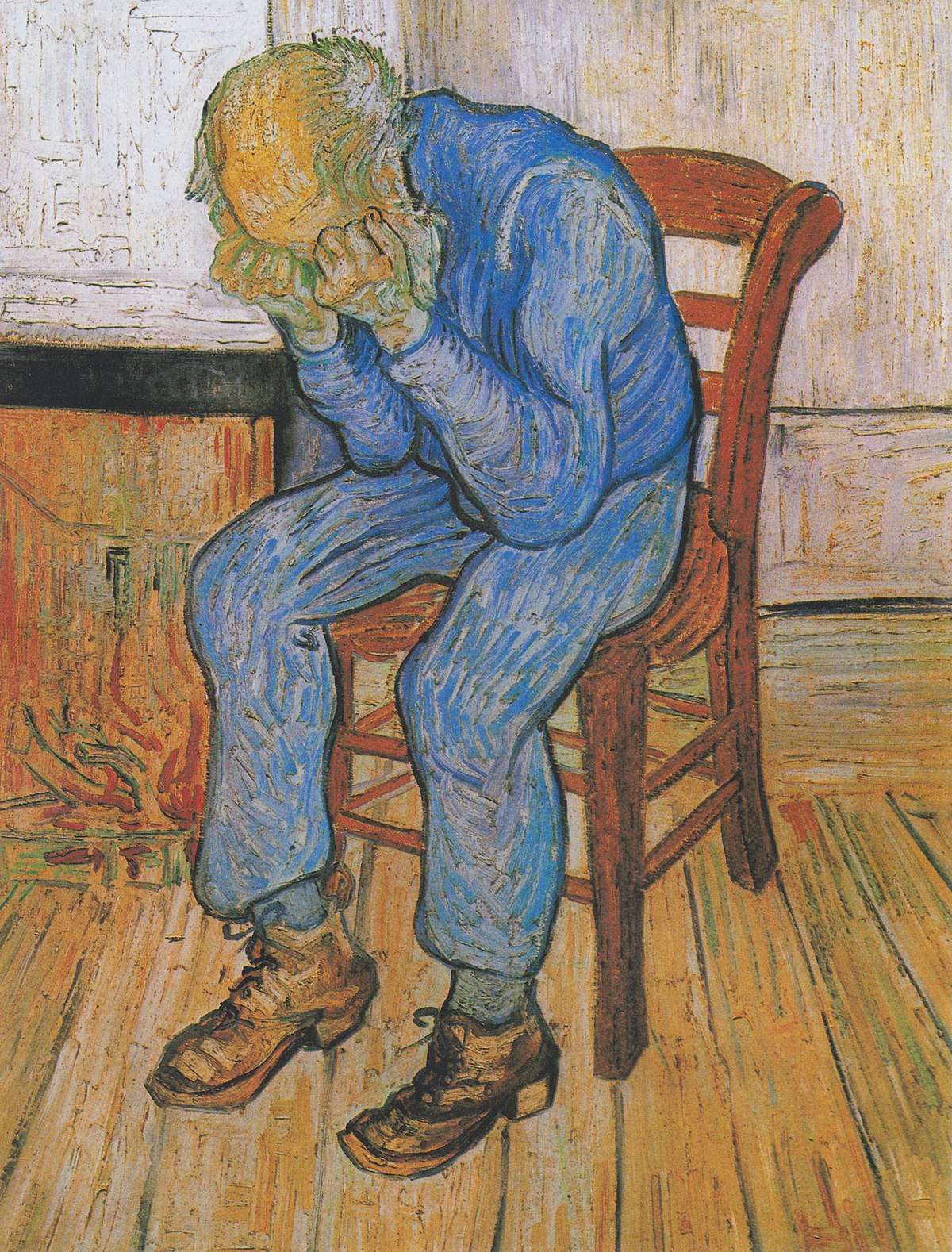

Last night, I read about interviewing psychiatric patients and writing up notes in the chart. So she sends me to interview a patient. I think of Vincent Van Gogh, an artist that had deep depression and psychotic episodes, cut off his ear, and committed suicide. He managed to become a famous painter… but only after he died. Who would I meet in this place?

There was the homeless gentleman that was picked up on the side of the road. I sat well on the other side of the room from him as he laid in the bed, clothes unkept and filthy, filled with body lice. I watched large bugs walk across his clothes. In the other rotations, I’d concentrate on how to treat the body lice, but that was someone else’s job. Now, I tried to delve into his psychosocial history. He didn’t really want to say much. Or rather, he didn’t say much that was helpful. I went back to his chart at the nursing station and got most of his information.

I interviewed another lady. She was there with depression. It was so bad that she could not even get out of bed. She was on medications now and starting to feel better. We talked about her family support, her plans on leaving here, how she felt. We had a pleasant conversation for about 20 minutes before she told me that she was worried. “About what?” I said. In a hushed voice, she told me about the chip that she once thought had been implanted in her head. “I used to think that they were listening to everything that I said.” She looked around the room cautiously. I asked if she still thought this was true. “Yes,” she said. We had a pause in conversation. Then, I moved on to talk about something else. But in that pause, I realized that crazy walks next to us on the street, hidden in the woman wearing a business suit, not just the homeless man yelling obscenities in the street all day.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

Mental illness has always lived in the recesses of society — talked about in hushed voices or not at all, moved behind closed doors, locked away in secure buildings. The diseases of the mind are sometimes more devastating than the body. How we define and what we consider mental illness has continued to change over time.

The first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, better known as the DSM was published in 1952. In medical school, I learned the categories of mental illness from the 4th edition, which has since been updated to DSM-5. This 947 page publication of the American Psychiatric Association continues to evolve as diseases and classifications come and go with changing attitudes, changing cultural norms, and changing attitudes to mental health and treatment.

Categories and classifications help us to understand disease and determine which treatments might be best. However, the disease model loses the individual. When the DSM was released, psychiatry notes changed overnight from the story of the patient to the story of their disease and how they fit into a category of their illness.

What did we lose in this transition?